April 6, 2020

Beef market impacts from COVID-19 vary widely

By Derrell S. Peel, Oklahoma State University Extension livestock marketing specialist

Wholesale and retail beef markets have endured enormous upheaval since mid-March. Starting March 16, the surge in retail grocery buying put huge demands on retail supply chains resulting in dramatic and immediate spikes in wholesale beef prices. As shown in Table 1, the overall cutout jumped by nearly 19 percent in a matter of three days.

Wholesale prices continued to push higher until March 23, peaking at $257.32 cwt., up 23.6% from March 13 levels. Since then, the cutout has dropped more than 10% to $230.44/cwt on April 3. It is not clear exactly where the boxed beef cutout will settle out in the coming days. At the same time, the demand for food service has dropped sharply leading to a diverse set of impacts on various wholesale beef cuts.

Table 1. Choice Boxed Beef Cutout, $/cwt.

| Date | Price | % Change From Previous Day |

| 03/02/20 – 03/11/20 | Avg. $207.04 | |

| 03/12/20 | $206.01 | |

| 03/13/20 | $208.14 | +1.0 |

| 03/16/20 | $224.36 | +7.8 |

| 03/17/20 | $239.93 | +6.9 |

| 03/18/20 | $247.24 | +3.0 |

| 03/19/20 | $249.87 | +1.1 |

| 03/20/20 | $253.75 | +1.6 |

| 03/23/20 | $257.32 | +1.4 |

| 03/24/20 | $256.31 | -0.4 |

| 03/25/20 | $255.30 | -0.4 |

| 03/26/20 | $253.57 | -0.7 |

| 03/27/20 | $252.84 | -0.3 |

| 03/30/20 | $250.97 | -0.7 |

| 03/31/20 | $243.15 | -3.1 |

| 04/01/20 | $235.17 | -3.3 |

| 04/02/20 | $232.64 | -1.1 |

| 04/03/20 | $230.44 | -0.9 |

Table 2 shows the changes in weekly wholesale beef product prices since early March. Middle meats, which are dominated by restaurant demand, have dropped while end meats have surged on grocery demand. Prices for most steak items are lower including the tenderloin (189A), down 29 percent and ribeye (112A), down 7.7% since early March. Prices for the Petite tender (114F), a popular restaurant item, is down more than 32 percent. Short ribs (123A), a popular export item, are down 47% in price. Prices for loin strips (180), a popular summer grilling steak that is normally increasing seasonally at this time, is up more than 22%. Top sirloin (184), is a multi-purpose steak is used in both restaurants and at retail grocery, is priced nearly 13% higher.

At the same time, end meat prices, which are typically declining into the summer, are higher driven by grocery demand for value cuts and ground beef. Prices are sharply stronger for the shoulder clod (114A), up 49% and Chuck rolls (116A), up 32% along with Round items including the Top round (168), up 33%; outside round (171B), up 47% and eye of round (171C), up 25%.

Fast food restaurant demand is down, despite drive-thru service remaining open, resulting in less ground beef demand. Prices of fresh lean 50% trimmings, mostly used for food service ground beef demand are down 50% to the lowest level in 18 years. Fresh 90% lean trimming prices are up nearly 8% on indications that imported lean trimmings dropped in March. Grocery demand for ground beef is up as noted above; however, ground beef at retail more commonly uses chuck and round items rather than trimmings.

Table 2. Choice Wholesale Beef Prices, $/cwt.

| Beef Primal | Beef Subprimal | IMPS* | Weekly Price Avg. 3/06-3/13 | Weekly Price 4/3 | % Change |

| Rib | Ribeye | 112A | $735.22 | $678.54 | -7.7 |

| Chuck | Shoulder Clod | 114A | $211.85 | $316.11 | +49.2 |

| Petite Tender | 114F | $423.96 | $287.17 | -32.3 | |

| Chuck Roll | 116A | $266.95 | $352.77 | +32.2 | |

| Brisket | Brisket | 120A | $416.98 | $379.03 | -9.1 |

| Plate | Short Ribs | 123A | $424.48 | $224.67 | -47.1 |

| Round | Top Inside Round | 168 | $242.76 | $323.31 | +33.2 |

| Outside Round | 171B | $218.12 | $319.89 | +46.7 | |

| Eye of Round | 171C | $255.78 | $320.23 | +25.2 | |

| Loin | Strip | 180 | $565.00 | $691.73 | +22.4 |

| Top Sirloin | 184 | $292.85 | $329.51 | +12.5 | |

| Tenderloin | 189A | $929.90 | $655.67 | -29.25 | |

| Trim | Fresh 90 | $223.65 | $240.95 | +7.7 | |

| Fresh 50 | $57.48 | $28.49 | -50.4 |

*Institutional Meat Purchase Specifications

Body condition score at calving is the key to young cow success

By Glenn Selk, Oklahoma State University Emeritus Extension animal scientist

Research data sets have shown conclusively that young cows that calve in thin body condition but regain weight and condition going into the breeding season do not rebreed at the same rate as those that calve in good condition and maintain that condition into the breeding season. The following table from Missouri researchers illustrates the number of days between calving to the return to heat cycles depending on body condition at calving and body condition change after calving.

Predicted number of days (d) from calving to first heat as affected by body condition score at calving and body condition score change after calving in two-year-old beef cows. (Body condition score scale: 1 = emaciated; 9 = obese) Source: Lalman, et al. 1997

| Body Condition Score Change in 90 Days After Calving | |||||||

| Condition score at calving | -1 | -.5 | 0 | +.5 | +1.0 | +1.5 | +2.0 |

| BCS = 3 | 189d | 173d | 160d | 150d | 143d | 139d | 139d |

| BCS = 4 | 161d | 145d | 131d | 121d | 115d | 111d | 111d |

| BCS = 5 | 133d | 116d | 103d | 93d | 86d | 83d | 82d |

| BCS = 5.5 | 118d | 102d | 89d | 79d | 72d | 69d | 66d |

Notice that none of the averages for cows that calved in thin body condition were recycling in time to maintain a 12-month calving interval. Cows must be rebred by 85 days after calving to calve again at the same time next year. This data clearly points out that young cows that calve in thin body condition (BCS 3 or 4) cannot gain enough body condition after calving to achieve the same rebreeding performance as two-year-old cows that calve in moderate body condition (BCS 5.5) and maintain or lose only a slight amount of condition. The moral of this story is: “Young cows must be in good (BCS 5.5 or better) body condition at calving time to return to estrus cycles soon enough after calving to maintain a 365-day calving interval.”

Oklahoma scientists used eighty-one Hereford and Angus x Hereford heifers to study the effects of body condition score at calving and post-calving nutrition on rebreeding rates at 90 and 120 days post-calving. Heifers were divided into two groups in November and allowed to lose body condition or maintain body condition until calving in February and March. Each of those groups was then re-divided to either gain weight and body condition post-calving or to maintain body condition post-calving.

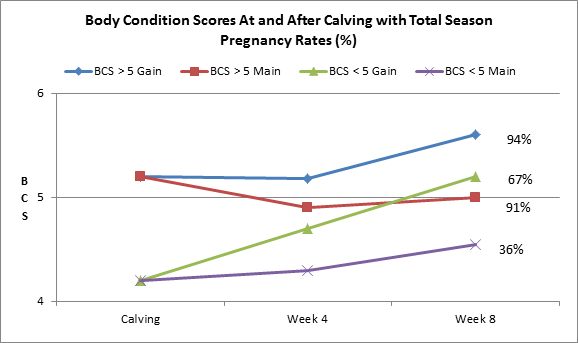

Figure 1 illustrates the change in body weight of heifers that calved in a body condition score greater than 5 or those that calved in a body condition score less than or equal to 4.9. The same pattern that has been illustrated in the other experiments is manifest clearly with these heifers.

Thin heifers that were given ample opportunity to regain weight and body condition after calving actually weighed more and had greater body condition by eight weeks than heifers that had good body condition at calving and maintained their condition into and through the breeding season.

However, the rebreeding performance (on the right side of the legend of the graph) was significantly lower for those that were thin (67%) at parturition compared to heifers that were in adequate body condition at calving and maintained condition through the breeding season (91%).

Again, post-calving increases in energy and therefore, weight and body condition gave a modest improvement in rebreeding performance, but the increased expense was not adequately rewarded. The groups that were fed to “maintain” post-calving condition and weight received four pounds of cottonseed meal supplement (41% Crude Protein) per day. The cows in the “gain” groups were fed 28 pounds a day of a growing ration (12% CP). Both groups had free choice access to grass hay (personal communication). The improvement in reproductive performance (67% pregnant vs 36% pregnant) of the thin two-year-old heifers may not be enough to offset the large investment in post-calving feed costs. Pre-calving feed inputs required to assure the heifers were in adequate body condition at calving would be substantially less than the feed cosst per head that was spent on the thin heifers after calving.

Figure 1. Post-calving body condition change of heifers with body condition >5 or <5 at calving and fed to gain or maintain weight. 120-day pregnancy rates (%) are indicated on the right side of the graph lines. Bell, et al. 1990

These data sets have shown conclusively that young cows that calve in thin body condition but regain weight and condition going into the breeding season do not rebreed at the same rate as those that calve in good condition and maintain that condition into the breeding season. Make certain next winter that the supplement program is adequate for your young cows to be in good body condition next spring.

Cow-Calf Corner is a weekly newsletter by the Oklahoma Cooperative Extension Agency.