Source: Cow-Calf Corner is a weekly newsletter by the Oklahoma Cooperative Extension Agency

Dec. 14, 2020

U.S. protein export markets

By Derrell S. Peel, Oklahoma State University Extension livestock marketing specialist

U.S. global meat protein exports have continued to evolve in 2020. Some of the changes this year reflect ongoing trends in global meat markets but the COVID-19 pandemic has also affected protein trade. Table 1 shows the top twelve export markets for beef, pork and broilers for the first ten months of 2020; their share of total exports; and the year-to-date export total for the major meat proteins.

Beef exports for the year-to-date through October are down 5.3% year over year after dropping sharply in May and June and then recovering from July to October. Total pork exports in 2020 are up 19.9%, driven by exceptionally strong exports to China, along with Taiwan and Hong Kong. Broilers exports so far in 2020 are up 4.2% year over year, with exports to Mexico, the largest market nearly unchanged from one year ago, but up sharply to China.

Mexico is arguably the market most impacted by COVID-19 from a U.S., and specifically a beef, perspective. Exports of beef to Mexico are down 37.9% year over year, with declines from last year every month in 2020. Mexico is suffering a devastating recession, the result of current federal policies aggravated by the pandemic.

The biggest changes across all meat markets relate to China. China has dramatically increased protein imports in 2020 after suffering from the devastating loss of pork production due to African swine fever (ASF) in 2018-2019. So far this year, China has accounted for nearly 30% of U.S. pork exports. This follows a 16% share of U.S. pork exports to China in 2019. Pork exports to China represented less than seven percent of total pork exports from 2014-2018 but previously peaked at nearly 13% of annual exports in 2011.

China is the number two market for broiler exports in 2020. Broiler exports to China have been very low in recent years, though China did account for ten to eleven percent of U.S. broiler exports from 2006-2009.

China has been a rapidly growing market for global beef imports in recent years and is the largest beef importing country since 2018. This reflects underlying growth in beef demand in China, accentuated by the protein shortages due to ASF. China has been a minor market for U.S. beef but is growing rapidly. The China share of U.S. beef exports exceeded one percent for the first time in 2019 and is the no. seven beef export market at 2.9% of total beef exports thus far in 2020. Beef consumption in China is expected to continue growing and, assuming no additional political disruptions, China could be one of the top exports markets for U.S. beef in the next couple of years.

Broiler meat exports are heavily dominated by Mexico, with China increasing from zero exports in the first ten months of 2019 to the number two market in 2020, to supplement ASF related protein shortages. Broiler meat is exported to a vast array of smaller markets. It is interesting for example, that broiler exports to Cuba in 2020 have exceeded exports to Vietnam and Canada. The top twelve broiler export markets only account for about 68 percent of broiler exports (compared to 94+% of beef and pork exports).

Table 1. Top 12 U.S. Protein Export Markets, January – October 2020.

| Rank | Beef | % of Total | Pork | % of Total | Broiler | % of Total |

| 1 | Japan | 29.2 | China | 29.2 | Mexico | 20.5 |

| 2 | S. Korea | 23.7 | Mexico | 20.7 | China | 8.7 |

| 3 | Canada | 10.1 | Japan | 16.5 | Taiwan | 7.5 |

| 4 | Mexico | 9.4 | Canada | 8.1 | Cuba | 5.2 |

| 5 | Hong Kong | 7.2 | S. Korea | 6.8 | Vietnam | 5.0 |

| 6 | Taiwan | 7.0 | Australia | 3.3 | Canada | 4.6 |

| 7 | China | 2.9 | Colombia | 2.5 | Guatemala | 3.4 |

| 8 | Philippines | 1.2 | Dom. Republic | 1.6 | Georgia (Republic) | 3.1 |

| 9 | Indonesia | 1.2 | Chile | 1.6 | Angola | 2.9 |

| 10 | Vietnam | 1.1 | Philippines | 1.5 | S. Africa | 2.5 |

| 11 | Netherlands | 1.0 | Honduras | 1.4 | Colombia | 2.4 |

| 12 | Chile | 0.7 | Hong Kong | 0.9 | Philippines | 2.3 |

| Top 12 | 94.7 | 94.0 | 68.2 | |||

| Total* | 2,392.859 | 100 | 5,009.861 | 100 | 6,320.631 | 100 |

*All countries, million pounds, year-to-date

Global protein trade is expected to improve in 2021 with pandemic control anticipated and more stability generally in world economies. However, recessionary impacts of the pandemic will continue to present challenges in many countries, including the U.S. At this time, U.S. exports of beef, pork and broilers are all expected to show at least modest growth in the coming year.

Most passive immunity occurs in the first 6 hours

By Glenn Selk, Oklahoma State University Emeritus Extension Animal Scientist

Resistance to disease is greatly dependent on antibodies or immunoglobulins and can be either active or passive in origin. In active immunity, the body produces antibodies in response to infection or vaccination. Passive immunity gives temporary protection by transfer of certain immune substances from resistant individuals.

An example of passive immunity is passing of antibodies from dam to calf via the colostrum (first milk after calving). This transfer only occurs during the first few hours following birth. Research is indicating that successful transfer of passive immunity (the first day of life) enhances disease resistance and performance through the first two years of life including the feedlot phase.

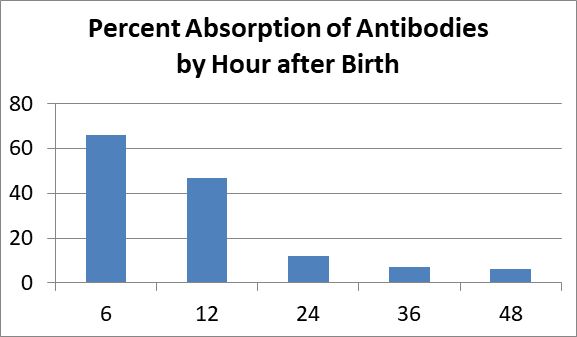

Timing of colostrum feeding is important because the absorption of immunoglobulin from colostrum decreases linearly from birth. “Intestinal closure” occurs when very large molecules are no longer released into the circulation and this occurs because the specialized absorptive cells are sloughed from the gut epithelium. In calves, closure is virtually complete 24 hours after birth. Efficiency of absorption declines from birth, particularly after 12 hours. Feeding may induce earlier closure, but there is little colostral absorption after 24 hours of age even if the calf is starved. This principle of timing of colostrum feeding holds true whether the colostrum is directly from the first milk of the dam or supplied by hand feeding the baby calf previously obtained colostrum.

Provide high risk baby calves (born to thin first calf heifers or calves that endured a difficult birth) at least two quarts of fresh or thawed frozen colostrum within the first six hours of life and another two quarts within another 12 hours. This is especially important for those baby calves too weak to nurse naturally.

Thaw frozen colostrum slowly in a microwave oven or warm water so as to not allow it to overheat. Thawing colostrum in a high power modern microwave at full power can cause denaturation of the protein. Therefore, if the colostrum is overheated and denaturation of the proteins occur, the disease protection capability of the immunoglobulin is greatly diminished. If at all possible, feed the calf natural colostrum first, before feeding commercial colostrum supplements.

If natural colostrum is not available, commercial colostrum replacers (those with 100 g or more of immunoglobulin per dose) can be given to the calf within the first six hours and repeated 12 hours later.

Cow-Calf Corner is a weekly newsletter by the Oklahoma Cooperative Extension Agency