Dec. 3, 2018

Cull cow market struggles to find a bottom

by Derrell S. Peel,Oklahoma State University Extension livestock marketing specialist

The cull cow market likely reached a seasonal low in November but it has been difficult to understand this market this year. Prices for Breaker cows in Oklahoma City averaged $50.13/cwt. in November, nearly 11 percent lower year over year, while Boning cows averaged $47.88/cwt., over 16 percent down from one year ago. Cull cow prices have been counter-seasonally lower year over year from May through October and have averaged 13-15 percent lower year over year for the last seven months.

Cull cow prices typically begin a slight recovery in December following the November seasonal low. Cull prices average a much stronger seasonal increase after Jan. 1, increasing by 6.7 percent in January from the November low; with February up 16.2 percent; March up 18.75 percent; April up 19.6 percent and May up 21.1 percent all from the November low. From current levels,this would suggest breaking cow prices of $53.47/cwt. in January; $58.26/cwt in February; $59.53/cwt. in March; $59.94 by April and $60.85/cwt. by May.

The question is whether the normal seasonal price increase can be expected given how weak the cull cow market has been since May of this year. One of the big factors contributing to weak cull cow prices has been weak cow boxed beef prices in the second half of 2018. In the last week of November, cow boxed beef prices were 7.8 percent lower than year earlier levels and have averaged 8.3 percent lower year over year since mid-year.

Increased supplies of cow beef is no doubt part of the cause for lower cow beef (and cull cow) prices. Total cow slaughter is projected to be up 7.2 percent in 2018 over last year, with a projected 9.6 percent year over year increase in beef cow slaughter and 4.9 percent increase in dairy cow slaughter. This is higher than the 2017 year over year increase of 6.3 percent in total cow slaughter. Total cow slaughter in 2019 is forecast to be flat to slightly lower year over year and should reduce the supply pressure a bit following three years of increasing cow slaughter. Beef imports, the bulk of which are processing beef that compete with cow beef, have been flat in 2018 and are forecast to decrease 3-5 percent in 2019.

While overall beef demand has been strong in 2018, the demand for cow beef is more uncertain. The bulk of cow beef is used for ground beef. It is possible that ground beef demand is facing more pressure from large supplies of pork and poultry compared to beef middle meats. Cow beef (90 percent lean) is mostly used to mix with fed trimmings (50 percent lean) to make the appropriate ratio of lean to fat in ground beef. Fed trimmings prices have remained close to year ago levels in contrast to the weakness in cow beef prices. Increased fed slaughter in 2018 and forecast larger slaughter again in 2019 would seem to suggest ample fed trimmings supply to support cow beef prices. However, growing exports of some fed products, such as navels, that historically were part of fed trimmings may be the reason for stronger fed trimmings prices relative to cow beef prices.

With all that said, I expect that a relative tightening of cow beef supplies will help cull cow prices to follow close to a normal seasonal increase going into 2019. Like all beef markets it is dynamic and evolving and bears watching in the coming months.

How many heifers to keep?

by Glenn Selk,Oklahoma State University Emeritus Extension animal scientist

Each year commercial cow-calf operations must decide how many replacement heifers are grown out to be put in the breeding pasture. Individual ranches must make the decisions about heifer retention based upon factors that directly affect their bottom line. Stocking rates may have changed over time due to increases in cow size. Droughts have caused herd sizes to fluctuate over time.

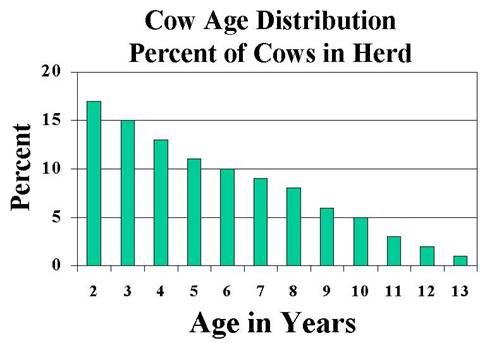

Matching the number of cattle to the grass and feed resources on the ranch is a constant challenge for any cow-calf producer. Also, producers strive to maintain cow numbers to match their marketing plans for the long term changes in the cattle cycle. Therefore, it is a constant struggle to evaluate the number of replacement heifers that must be developed or purchased to bring into the herd each year. As a starting place in the effort to answer this question, it is important to look at the “average” cow herd to understand how many cows are in each age category. The Dickenson North Dakota Research and Extension Center reported on the average number of cows in their research herd by age group for a period of over 20 years. The following graph depicts the “average” percent of cows in this herd by age group.

The above graph indicates that the typical herd will, “on the average”, calve out 17 percent new first-calf cows each year. Stated another way, if 100 cows are expected to produce a calf each year, 17 of them will be having their first baby. Therefore, this gives us a starting point in choosing how many heifers we need to save each year.

Next, we must predict the percentage of heifers that enter a breeding season that will become pregnant. The prediction is made primarily upon the nutritional growing program that the heifers receive between weaning and breeding. The rate at which heifers are grown between weaning and breeding will vary depending on the size of the operation, the land resources available, and the selection criteria desired by the cattle owner.

The rate of growth between weaning and breeding will determine the percentage of heifers cycling at the start of the breeding season. Researchers many years ago found that only half of heifers that reached 55 percent of their eventual mature weight were cycling by the time they entered their first breeding season. This data was reinforced with data from Oklahoma State University (Davis and Wettemann, 2009 OSU Animal Science Research Report).

Growing heifers at a slower rate between weaning and breeding would result in most of them weighing 55 percent of mature weight (or less) when the breeding season begins. If these heifers were exposed to a bull for a limited number of days (45-60), not all would have a chance to become pregnant during that breeding season. Therefore, it would be necessary to keep an additional 50 percent more heifers just to make certain that enough bred heifers were available to go into the herd.

Although the cost per heifer may be lower, there will be increased total inputs because of the increase in number of animals. Remember the increased number of heifers will require additional pasture, increased health costs, and increased breeding costs. If natural breeding is used, extra bull power may be necessary. If artificial insemination is the method of choice, the larger number of heifers will require increased synchronization and AI costs.

Heifers should be pregnancy checked as soon as possible and the open heifers marketed as stocker heifers. Hopefully most of the extra pasture, feed, and health inputs are recovered by the sale value of the open heifers.

However, if the heifers were grown at a more rapid rate and weighed 65 percent of their eventual mature weight, then 90 percent of them would be cycling at the start of the breeding season and a much higher pregnancy rate would be the result. Therefore, fewer heifers are needed. Even in the very best scenarios, a few heifers will be difficult or impossible to breed. Most experienced cow herd managers will always expose at least 10 percent more heifers than they need even when all heifers are grown rapidly and weigh at least 65 percent of the expected mature weight at bull turn-out or estrous synchronization.

The need to properly estimate the expected mature weight is important in understanding heifer growing programs. Cattle type and mature size has increased over the last half century. Rules of thumb that apply to 1000 pound mature cows very likely do not apply to your herd. Watch sale weights of culled mature cows from your herd to better estimate the needed size and weights for heifers in your program. Most commercial herds have cows that average about 1200 pounds or more. This requires that the heifers from these cows must weigh at least 780 pounds at the start of their first breeding season to expect a high percentage to be cycling when you turn in the bulls.

This discussion is meant to be a STARTING PLACE in the decision to determine the number of heifers needed for replacements. Ranchers must keep in mind the over-riding need to understand what forage base resources that they have available to them. If forage resources are already in consistently short supply, maintaining or increasing herd size may be counter-productive.

Cow-Calf Corner is a newsletter by the Oklahoma Cooperative Extension Agency.