Aug. 21, 2020

The first part of this article on derechos was written by Dr. Becky Bolinger. Dr. Bolinger is the Colorado assistant state climatologist and is based at Colorado State University. She is a frequent contributor to Livestock Wx, the U.S. Drought Monitor and tracks all things climate. A longer version of her derecho discussion will appear on Livestock Wx.

What is a “derecho” and what you should know about them

It’s been a week and a half since a derecho tore across Iowa, but the evidence of this very powerful storm remains – widespread devastation to corn crops, damage to buildings, thousands still without power, many homeless. This may be the first time you’ve heard the term derecho or witnessed the power of one, and you may be thinking 2020 is just bringing us new meteorological hazards. But the term was first coined in the late 19th century, and they’ve been part of meteorologists’ vocabulary since the 1980s. So, what are they? Where and when do they happen? Can we predict them?

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Storm Prediction Center has defined specific criteria that must be met for an event to be considered a derecho.

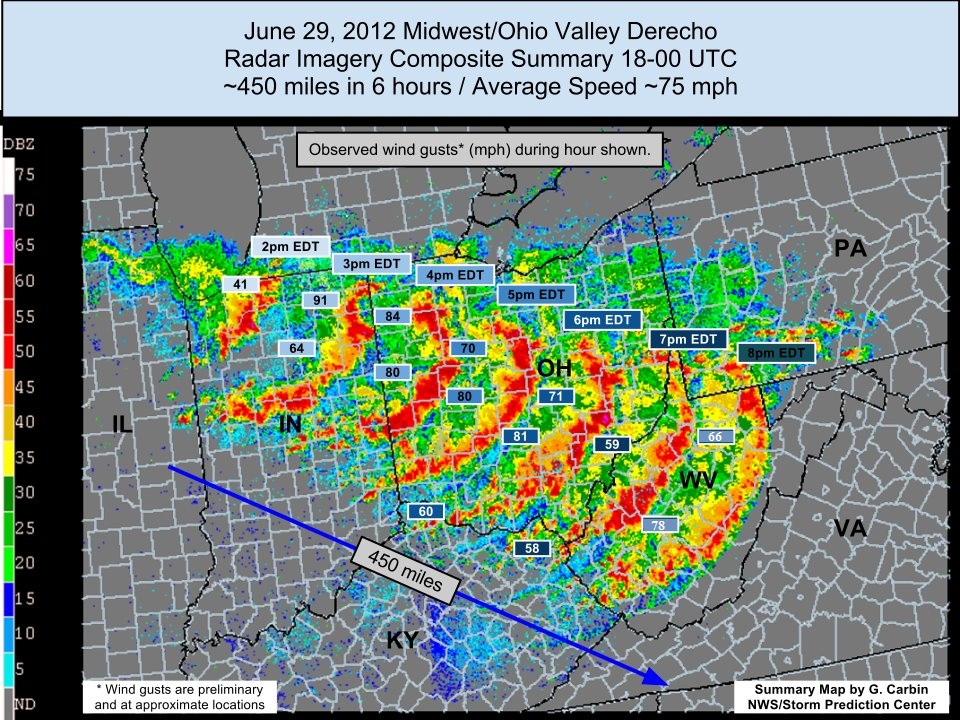

First, a concentrated area of convectively-induced (i.e. thunderstorm) wind gusts greater than 26 m/s (58 mph) would be observed over a major axis length of 400 km (almost 250 miles). The image below, from the National Weather Service, shows an example of a derecho in 2012. The radar imagery helps meteorologists assess the scope and structure of the event, and the numbers are the observed wind gusts during the event.

The potential winds and subsequent damage from a derecho can be equivalent to an EF-0 to EF-2 tornado (an EF-2 can have winds from 111-135 mph with considerable damage). But derechos are distinctly different from tornadoes. First, they are much more widespread. And the winds associated with them aren’t necessarily rotating, which is why you may hear the term “straight-line winds.” These wind speeds are partly due to how fast the storm is traveling.

Can meteorologists predict derechos?

With each passing year, numerical weather prediction is getting better and better. But predicting the potential formation of a derecho is particularly challenging. The Storm Prediction Center and National Weather Service offices are very good at identifying areas where severe weather is likely to occur a day or two in advance. Similar to the difficulty in predicting which thunderstorm will produce a tornado, it’s challenging to know which line of storms may organize into a larger scale derecho.

Once a derecho has formed, there are new challenges with forecasting its speed, strength and direction (based on the complexities of the storm itself, but also of the surrounding environment). But it has been possible to warn people several hours ahead of an advancing derecho so that precautions can be taken.

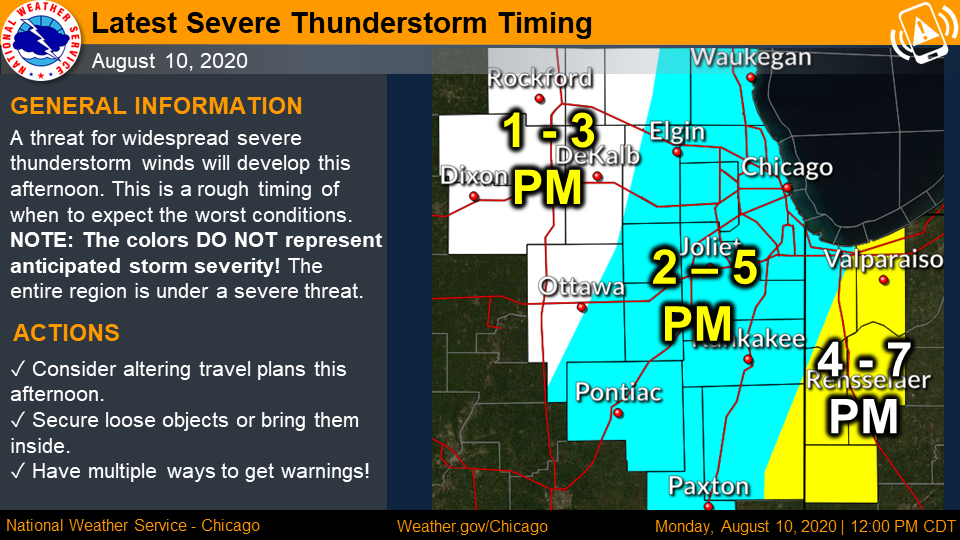

Take the Aug. 10 derecho, for example. On Aug. 9, NOAA did not see an indication of potential for derecho development, though they did note there was marginal risk for severe thunderstorm activity associated with a cold front moving across the region. By the morning of Aug. 10, forecasters were aware of the developing situation and had placed eastern Iowa and northern Illinois in an area of enhanced risk for severe thunderstorms. By noon, the Chicago National Weather Service office had released this forecast of the arrival of the derecho storm, well in advance of the 2 p.m. to 5 p.m. arrival.

This is a good reminder to always be prepared for severe weather in the summer months. Check your local National Weather Service office’s website daily; keep up-to-date on the Storm Prediction Center’s maps of where the risk for severe weather is expected over the next couple of days; and get a good radar app on your phone to keep your eye on any storms headed your way (my personal favorite is RadarScope, you can find it on your platform’s app store).

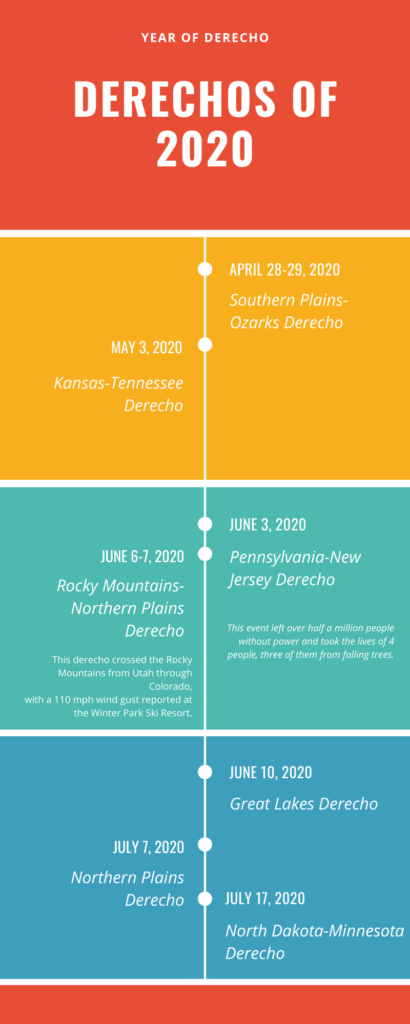

The derechos of 2020

It’s been an active year for derechos (because of course, 2020). According to Wikipedia, the following derechos have occurred this year:

La Niña influences Sep-Oct-Nov outlooks

Last week NOAA updated its El Niño/La Niña Forecast (aka ENSO Forecast). NOAA increased the odds of La Niña development to ~60% during the fall of 2020 and a 55% chance of continuing through winter 2020-21. The increased odds of La Niña have influenced the Seasonal Outlooks that were released on Thursday, Aug. 20 by NOAA. Both the temperature and precipitation outlook maps are below.

Sep-Oct-Nov temperature outlook

For Sep-Oct-Nov 2020, the outlook shows a tilt in the odds for above normal temperatures for the entire Contiguous U.S. The odds are based on model output but also on what is being observed in the Pacific Ocean and the increase in the odds for a La Niña in the fall. The highest odds for above normal temperatures are in the Northeast and the Southwest.

There is less certainty in the Northwest and Northern Great Plains and part of the reason for that is the increased odds of a fall La Niña. Taking a look at the outlook going out to the Jan-Feb-Mar 2021 timeframe, NOAA is favoring below normal temperatures from the Pacific Northwest through parts of the Northern Plains.

2021 is a long way out so don’t take these outlooks too seriously… yet.

Sep-Oct-Nov precipitation outlook

Like the temperature outlook, the potential for La Niña developing through the winter of 2020-21 played a role in the outlook for precipitation. For Sep-Oct-Nov, there is a tilt in the odds for above normal precipitation in the Southeast and Pacific Northwest while the odds favor below normal precipitation for the Southwest and Southern Plains.

NOAA is betting the fall and winter will reflect a typical La Niña pattern so the odds for above normal precipitation have increased across the Pacific Northwest with a drier signal into the Great Basin, while the winter seasons odds for below normal precipitation across the entire southern tier of the Contiguous U.S. have increased. Again, winter is a long way out so things could change.

We’ll keep monitoring conditions, but it is looking more likely we could get another visit from La Niña this fall and winter.