Nov. 26, 2018

Beef cow herd dynamics returning to normal

by Derrell S. Peel, Oklahoma State University Extension livestock marketing specialist

The beef cattle industry has experienced some extraordinary dynamics in the past decade that provoked unprecedented volatility and record price levels. An aborted expansion attempt in the mid-2000s was followed by more herd liquidation through 2010; followed by even more drought-forced liquidation in 2011-2013 that pushed cow numbers two million head lower than anyone planned or the market needed. This provoked a dramatic market response to jump-start herd expansion and pushed the parameters of herd dynamics to extreme limits. Only now are herd dynamics beginning to return to normal levels.

The beef cow herd likely increased less than one percent year over year in 2018 to a projected Jan. 1, 2019, level of about 31.9 million head. This may be the cyclical peak in herd inventory, or very close to it. From the 2014 low of 29.1 million head, this cyclical expansion has increased the beef cow herd by 2.8 million head or 9.6 percent over five years. The last full cyclical herd expansion occurred in 1990-1996 resulting in an 8.8 percent herd expansion in six years.

Part of herd expansion is heifer retention, commonly measured by the Jan. 1 inventory of beef replacement heifers as a percent of the beef cow inventory. This percentage has averaged 17.6 percent over the last 30 years. The percentage increases above average during herd expansion and drops below average during herd liquidation. From a recent low of 16.6 percent in 2011, the replacement heifer percentage increased rapidly and averaged over 20 percent from 2015-2017. The peak of 21 percent in 2016 was the highest heifer replacement percentage since historic herd growth in the 1960s. The percentage dropped to 19.3 percent in 2018 and is projected to drop to 18.0-18.5 percent in 2019; still above average but returning closer to normal.

Increased heifer retention reduces the number of heifers in the slaughter mix. This can be measured several ways including the ratio of steer to heifer slaughter. Fewer heifers slaughtered increases the ratio of steers to heifers slaughtered. This ratio has averaged 1.71 over the last 30 years. The ratio increased to 2.143 in 2016, the highest levels since the early 1970s, and has been moving back to more typical levels since. The ratio dropped to 1.948 in 2017 and is projected to drop to about 1.83 in 2018. Heifer slaughter was up year over year by 11.9 percent in 2017 and is projected to be up by 6.0-6.5 percent again in 2018. This is the process of heifer slaughter returning to normal levels as heifer retention slows.

The other part of herd expansion is reduced cow culling. Annual beef cow slaughter as a percent of Jan. 1 beef cow inventory has averaged 9.5 percent over the last 30 years. Beef cow slaughter dropped sharply from 2012 – 2015 resulting in a record low beef cow culling percent of 7.63 percent in 2015 and a below average culling rate from 2014-2017. Beef cow slaughter has seen annual increases averaging 11 percent year over year since 2016, including a projected 10.1 percent year over year increase in 2018. At the current rate, beef cow culling in 2018 will be 9.7 percent, very close to the long-term average culling rate. Herd expansion significantly reduces the role of females in beef production. The sum of heifer plus cow slaughter as a percent of total slaughter reached a 40-plus year low in 2016 but is slowly returning closer to normal levels in 2018.

Should the beef cow herd stabilize near current levels, as it appears now, we would expect to see the cattle slaughter mix return to long term average levels. Total 2018 cattle slaughter is projected at 33.15 million, including steer slaughter at 51.3 percent of the total compared to a 50.7 percent long-term average; heifer slaughter of 28.0 percent (29.9 percent average); and total cow slaughter of 19.0 percent (17.7 percent average). This includes beef cow slaughter projected at 9.4 percent of total cattle slaughter in 2018 compared to a 9.3 percent long term average. Bull slaughter is projected at 1.7 percent of total slaughter, close to the long term average of 1.8 percent.

Body condition score at calving is the key to young cow success

by Glenn Selk, Oklahoma State University Emeritus Extension animal scientist

Most areas of Oklahoma have had adequate summer forage to allow pregnant replacement heifers to be in excellent body condition going into late fall and winter. Now producers are faced with the challenge of maintaining body condition on the replacement heifers through the calving season and into next spring. As the title of this article suggests, “Body condition score at calving is the key to success.” Body condition (or amount of fatness) is evaluated by a scoring system that ranges from 1 (severely emaciated) to 9 (very obese).

Research data sets have shown conclusively that young cows that calve in thin body condition but regain weight and condition going into the breeding season do not rebreed at the same rate as those that calve in good condition and maintain that condition into the breeding season. The following table from Missouri researchers illustrates the number of days between calving to the return to heat cycles depending on body condition at calving and body condition change after calving.

Predicted number of days (d) from calving to first heat as affected by body condition score at calving and body condition score change after calving in two-year-old beef cows. (Body condition score scale: 1 = emaciated; 9 = obese) Source: Lalman, et al. 1997

| Body Condition Score Change in 90 Days After Calving | |||||||

| Condition score at calving |

-1 | -.5 | 0 | +.5 | +1.0 | +1.5 | +2.0 |

| BCS = 3 | 189 d | 173 d | 160 d | 150 d | 143 d | 139 d | 139 d |

| BCS = 4 | 161 d | 145 d | 131 d | 121 d | 115 d | 111 d | 111 d |

| BCS = 5 | 133 d | 116 d | 103 d | 93 d | 86 d | 83 d | 82 d |

| BCS = 5.5 | 118 d | 102 d | 89 d | 79 d | 72 d | 69 d | 66 d |

Notice that none of the averages for cows that calved in thin body condition were recycling in time to maintain a 12 month calving interval. Cows must be rebred by 85 days after calving to calve again at the same time next year. This data clearly points out that young cows that calve in thin body condition (BCS=3 or 4) cannot gain enough body condition after calving to achieve the same rebreeding performance as two-year old cows that calve in moderate body condition (BCS = 5.5) and maintain or lose only a slight amount of condition. The moral of this story is: “Young cows must be in good (BCS = 5.5 or better) body condition at calving time to return to estrus cycles soon enough after calving to maintain a 365 day calving interval.”

Oklahoma scientists used eighty-one Hereford and Angus x Hereford heifers to study the effects of body condition score at calving and post-calving nutrition on rebreeding rates at 90 and 120 days post-calving. Heifers were divided into two groups in November and allowed to lose body condition or maintain body condition until calving in February and March. ach of those groups was then re-divided to either gain weight and body condition post-calving or to maintain body condition post-calving.

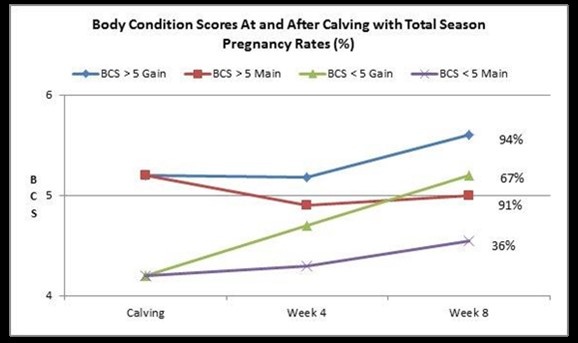

Figure 1 illustrates the change in body condition and weight of heifers that calved in a body condition score greater than 5 or those that calved in a body condition score less than or equal to 4.9. The same pattern that has been illustrated in the other experiments is manifest clearly with these heifers. Thin heifers that were given ample opportunity to regain weight and body condition after calving actually weighed more and had greater body condition by eight weeks than heifers that had good body condition at calving and maintained their condition into and through the breeding season.

However, the rebreeding performance (on the right side of the legend of the graph) was significantly lower for those that were thin (67 percent) at parturition compared to heifers that were in adequate body condition at calving and maintained condition through the breeding season (91 percent).

Again, post-calving increases in energy and therefore weight and body condition gave a modest improvement in rebreeding performance, but the increased expense was not adequately rewarded. The groups that were fed to “maintain” post-calving condition and weight received 4 lb of cottonseed meal supplement (41 percent Crude Protein) per day.

The cows in the “gain” groups were full-fed a complete growing ration (12 percent CP). Both groups had free choice access to grass hay. The improvement in reproductive performance (67 percent pregnant vs 36 percent pregnant) of the thin two-year-old heifers may not be enough to offset the large investment in post-calving feed costs. Pre-calving feed inputs required to assure the heifers were in adequate body condition at calving would be substantially less than the costs per head that was spent on the thin heifers after calving.

Figure 1. Post-calving body condition change of heifers with body condition >5 or <5 at calving and fed to gain or maintain weight. 120 day pregnancy rates (%) are indicated on the right side of the graph lines. Bell, et al. 1990

Other data sets have shown conclusively that cows that calve in thin body condition but regain weight and condition going into the breeding season do not rebreed at the same rate as those that calve in good condition and maintain that condition into the breeding season. Make certain that the supplement program is adequate for your young cows to be in good body condition this spring.

Cow-Calf Corner is a newsletter by the Oklahoma Cooperative Extension Agency.