This week’s drought summary

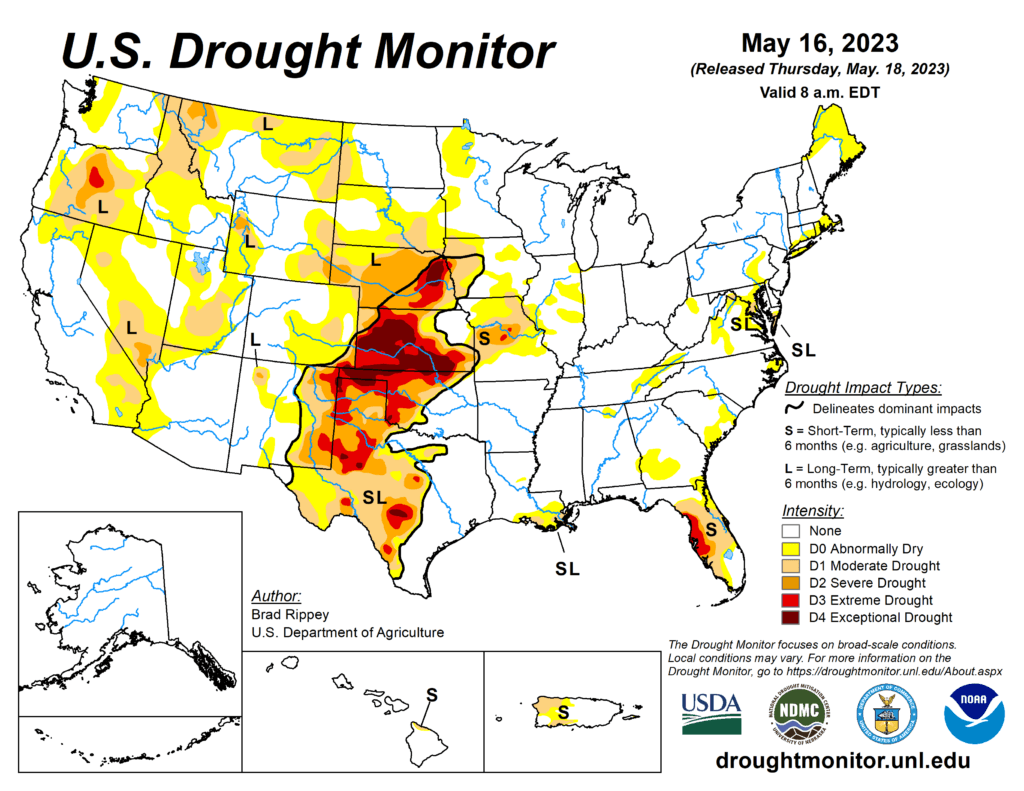

A complex, slow-moving storm system delivered heavy rain across much of the nation’s mid-section, but largely bypassed some of the country’s driest areas in southwestern Kansas and western Oklahoma, as well as neighboring areas. Still, the rain broadly provided much-needed moisture for rangeland and pastures, immature winter grains, and emerging summer crops. Significant rain spread into other areas, including the southern and western Corn Belt and the mid-South, generally benefiting crops but slowing fieldwork and leaving pockets of standing water. Excessive rainfall (locally 4 to 8 inches or more) sparked flooding in a few areas, including portions of the western Gulf Coast region. Little or no rain fell across much of the remainder of the country, including southern Florida, the Northeast, the Great Lakes region, and an area stretching from California to the southern Rockies. Warmth in advance of the storm system temporarily boosted temperatures considerably above normal across parts of east-central Plains, western Corn Belt, and upper Great Lakes region. Meanwhile, record-setting heat developed in the Pacific Northwest, setting several May temperature records.

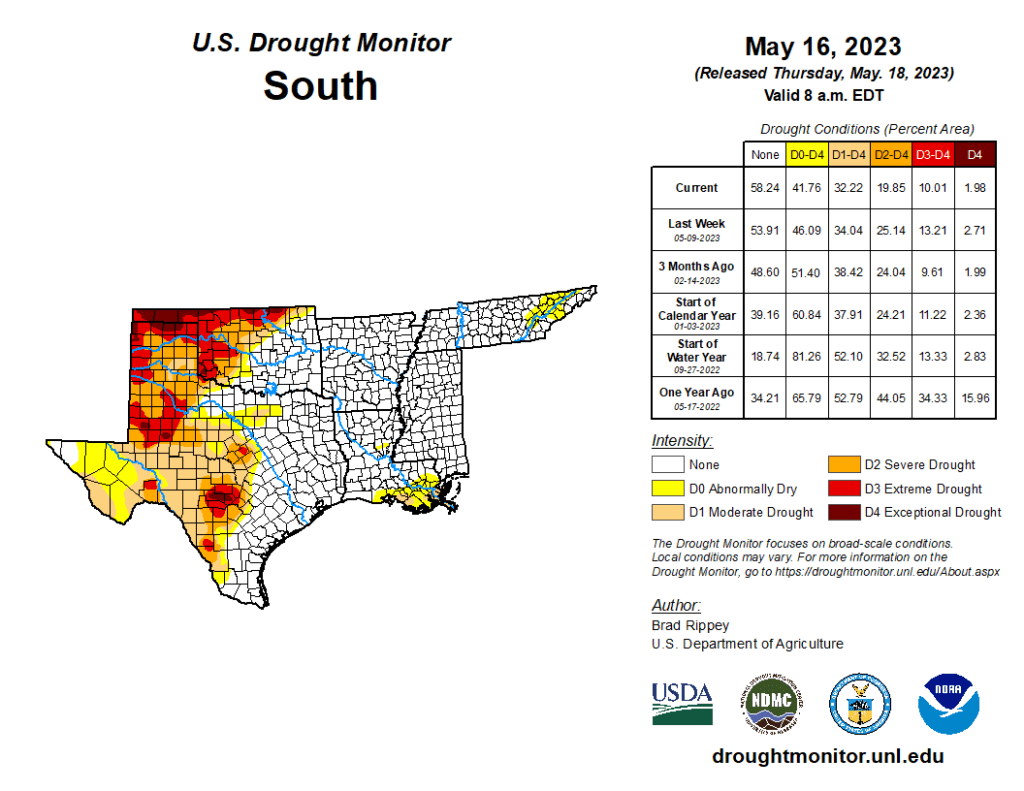

South

Most of the region remained free of drought, but moderate to exceptional drought (D1 to D4) persisted in parts of central and western Texas and across the northwestern half of Oklahoma. During the drought-monitoring period, ending on the morning of May 16, extremely heavy rain drenched the western Gulf Coast region, especially near the central Texas coast. On May 10, Palacios, Texas, measured 6.21 inches of rain—part of a very wet stretch that included an additional 3.93 inches on May 13-14. Heavy showers extended northeastward into southeastern Oklahoma, northern Louisiana, Arkansas, and western Tennessee. By May 14, the U.S. Department of Agriculture reported that topsoil moisture was rated 30% surplus in Arkansas, along with 29% in Louisiana. Farther west, however, serious drought impacts persisted, despite spotty showers. Statewide in Texas, rangeland and pastures were rated 51% very poor to poor on May 14. Any rain was generally too late for the southern Plains’ winter wheat, which is quickly maturing. More than half of the wheat—52 and 51%, respectively, in Texas and Oklahoma—was rated very poor to poor by mid-May. A recent estimate by the U.S. Department of Agriculture indicated that 32.6% of the nation’s winter wheat will be abandoned—highest since 1917—including 70.1% of the Texas crop.