How John R. Erickson left the Ivy League to become a cowboy and inspire generations with Hank the Cowdog.

By Elyssa Foshee Sanders

John R. Erickson wasn’t much of a reader growing up.

The cowboy, prolific voice actor and author of more than 100 books, including the bestselling children’s series, Hank the Cowdog, says he preferred to listen to his mother’s stories about life in rural Texas — stories that laid the foundation for his writing career.

“I don’t know if I was dyslexic at a time when nobody knew what that was, but reading was very difficult for me,” Erickson recalls. “I write those Hank books for fourth-grade donkey boys who hate books and don’t want to read.”

However, schoolchildren were not initially Erickson’s intended audience.

“I wasn’t trying to write stories for children. As a matter of fact, the original audience for Hank was mostly adult males involved in agriculture — readers of The Cattleman magazine.”

Hank the Cowdog, the crime-solving mutt and self-appointed Head of Ranch Security for a cattle operation in the Texas Panhandle, beloved by generations of Texans and even the most reluctant readers, made his debut in the June 1981 issue of The Cattleman.

Editor-in-chief Dale Seagraves paid Erickson $150 for the story.

A struggling novelist, cowboy and father of three young children, Erickson had resorted to churning out magazine articles at a furious pace to make ends meet.

“I was writing entire stories in one morning, really cranking them out,” Erickson recalls. “I was making very little in cowboy wages and needed the money. I was writing for money, not for literature.”

One such story, Diary of a Bronc, is based on Erickson’s ill-fated experience breaking a five-year-old gelding named Casey at the LZ Ranch south of Perryton.

“It starts off with the horse saying, ‘Casey’s my name, being an outlaw is my game. I’m five years old and never been rode. The first man that tries me is gonna get throwed,” Erickson recites in the gravelly, contemptuous drawl of a wild west desperado taunting the town sheriff before a shootout.

“It’s very biblical because it’s a story of pride — the sin of pride and the agonizing process of attaining knowledge and wisdom — and every detail came from the experience of breaking that horse,” he says.

Erickson had never written from the point of view of an animal, and he enjoyed it so much that he wrote another story the next morning.

“I remembered a dog that I had known when I worked up in the Oklahoma Panhandle,” Erickson says. “He was an Australian Shepherd named Hank, and he was about five bales short of a full load of brains.

“He thought he was Head of Ranch Security, and when we gathered cattle for branding, he would stand in the gate and bark so that we couldn’t get the cattle where we wanted them. Cowboys were screaming at him, ‘Get out of the gate! Go to the pickup! Go to the house!’ We would’ve throttled him if we’d had half a chance.”

Inspired, Erickson penned Confessions of a Cowdog, wherein Hank and his sidekick, Drover, terrorize cattle, duel with coyotes, and gorge themselves on livestock medication. He submitted the story to The Cattleman and set it aside without much more thought.

A few months later, during a reading at the Perryton Rotary Club, Erickson decided to perform Confessions of a Cowdog instead of his go-to story, Diary of a Bronc.

The audience’s reception floored him.

“I was astounded by the reaction,” he recalls. “The crowd just roared with laughter.”

After the reading, a man from the audience approached Erickson and implored him to keep writing about Hank.

“If he hadn’t told me that, I’m not sure I ever would have recognized the magic in those characters — I might never have done anything else with them,” Erickson says. “I never dreamed that Hank would become a star or that I would end up working for him, but that’s the way it turned out.

“Hank just kind of fell out of the sky. I wasn’t looking for him.”

The Magic of Hank

Hank the Cowdog, at once foolish and deeply philosophical, his grasp of the English language tenuous and his internal dialogue littered with malapropisms and misleading hyperboles, alternates between the obtuse and the eloquent.

“To me, he’s a dog, not a human wearing a dog suit, and I get my ideas watching my dogs,” Erickson says. “Hank is dead-serious about being Head of Ranch Security. When he barks at a low-flying B-52 bomber, he’s convinced that it’s a Silver Monster Bird that eats cows. Your average ranch dog in Texas puts a lot of effort into looking ridiculous. It’s not an easy job.”

In The Case of the Car-Barkaholic Dog, Hank and Drover employ a covert operation known as Syruptishus Loaderation: “a secret and rather technical procedure for climbing aboard a pickup that is heading for town, when the driver of the alleged pickup would be less than thrilled if he knew that he was hauling dogs.”

“You’ll notice that the root of the first word is ‘syrup,’” Hank explains to readers. “Perhaps you’ve observed the way syrup moves. It doesn’t run or fall or hop or splash. It oozes along its course, which is a sneaky and stealthy way of moving. Things that ooze are usually up to no good, and by simple logic it follows that most of your syrups are up to no good.

“Hence, from the root ‘syrup,’ we build a new and exciting word that means ‘sneaky and stealthy.’”

It’s this wholesome, cross-sectional appeal that continues to draw generations of fans to Erickson’s book signings and live readings.

“A lot of humor these days is not really humor, it’s ridicule,” Erickson says. “It’s motivated by anger, and I’ve managed to keep that out of the Hank stories. I want gentle, organic humor. It’s the kind of humor that cuts across national and language barriers.”

When Hank isn’t being outwitted by Pete the Barncat, rousing the ire of his owners, High Loper and Sally May, or berating Drover for his cowardice, he’s tending to cattle alongside Slim Chance, a lanky, banjo playing, tobacco chewing cowboy whom Erickson modeled after himself.

“There’s definitely a strong link between me and Slim Chance, and from the very first story that ran in The Cattleman, Gerald Holmes, the artist, drew Slim as a caricature of me,” Erickson says.

“Slim lives on boiled turkey necks and chicken gizzards because they’re cheap and easy to fix. As a bachelor, that’s how I lived. Like Slim, I didn’t wash my dirty dishes. I put them in the freezer so they wouldn’t decompose in the sink.

“Like Slim, I talk to my dogs and pull pranks on them. Hank often wonders, ‘Do normal people behave this way around their dogs?’ Probably not, but Slim does and so do I.”

But before Erickson became a $500-dollar-a-month cowboy and developed his fictional alter-ego, he longed to leave West Texas for the bright lights of New York or Boston and write literature in the tradition of Hemingway.

Wanderlust

“Growing up in Perryton, it was just kind of assumed that if you had any kind of talent or ambition, you wouldn’t go back home,” Erickson says. “We heard a lot about Harvard and I was curious to know whether a kid from a small town in the Panhandle could compete in that exotic world.”

After graduating from high school in 1962, Erickson moved away from Perryton to attend the University of Denver. He spent a summer working at a church in New York City before returning to Texas to complete his bachelor’s degree at the University of Texas, where he met his soon-to-be wife, Kristine Dykema.

In 1966, Erickson received a fellowship to study theology at a seminary of his choice and seized the opportunity to enroll in Harvard Divinity School.

During his second year at Harvard, Erickson took a fiction writing course in which he “didn’t learn much of anything,” he says, but which ignited a love for writing that has never waned.

“I started a disciplined life of writing when I got married — that brought some discipline into my life — and I started writing every morning, which is a pattern I’ve continued to the present day.”

Seven days a week, before the sun rises at the M-Cross Ranch — his and Kris’s property north of the Canadian River Valley — Erickson retreats to his office and spends four to five hours in front of his laptop drafting magazine articles, responding to fan mail, writing non-fiction books and planning Hank’s next mission.

He limits himself to writing two new Hank the Cowdog novels annually.

“I’m fanatical about it,” Erickson says of his morning routine. “I was not very disciplined until I married a woman with high standards, and it really turned my life upside-down. Part of my incentive was to hide from her the awful truth: I secretly longed to be a bum.

“Also, I had a sense of higher purpose and thought it was important for me to become as much of a writer as I could, and I had stories that were worth sharing.”

Back to His Roots

In the winter of 1968, three credits shy of earning his master’s degree from Harvard, Erickson had an epiphany: His longtime desire to study, work and live among the big city, Ivy League intelligentsia had all but evaporated.

“I discovered that theology was not my language, and also that I couldn’t wash Texas off,” Erickson says. “I realized in my second year that I was not part of that world and never would be, and I needed to get back to Texas and figure out what to do.

“Growing up looking at the distant, bright lights, I never thought about community being important. But when Kris and I moved back to Perryton, we’d lived through a decade of social change, unrest and foment, and the stability of a little quiet town where you knew your neighbors and went to church seemed pretty appealing to us at that time.”

Erickson and Kris uprooted their lives once again and returned to West Texas, where Erickson moonlighted as a bartender, a handyman, a carpenter and eventually a cowboy in the Oklahoma and Texas Panhandles while trying to get his novels published.

“I wrote novels for four or five years and sent them off to New York publishers,” Erickson says. “I didn’t know any other way of doing it — that’s the way Hemingway did it — so I was trying to get the approval of New York writers and editors and publishers, and I got nothing but rejection slips.”

At the suggestion of a friend, he decided to shed his Harvard-instilled notions of what constituted high literature and write about what he knew and loved: being a cowboy.

Erickson poured his wealth of knowledge about ranching, gained during the four years he spent working at the Crown Ranch in Oklahoma, into a book called Panhandle Cowboy, published by the University of Nebraska Press in 1980. Then-unknown author Larry McMurtry penned the forward, five years before the publication of Lonesome Dove.

A year later, Erickson authored The Modern Cowboy, a spiritual successor to Panhandle Cowboy, in which he explains ranching and cowboy work in meticulous detail. The Modern Cowboy explores virtually every aspect of cowboying, from the economics of ranching, to attire — “[The cowboy’s] dress depends on weather, chores, and vanity,” Erickson writes — to married life on the ranch.

“It’s a very deep account of what cowboys do, what ranching’s all about — the skills, the tools, cowboy work, horsemanship — but it had a very small audience and it lived in obscurity,” he explains.

Simmering in the background were Erickson’s real-life, humor-filled stories published in The Cattleman and the budding celebrity of Hank the Cowdog.

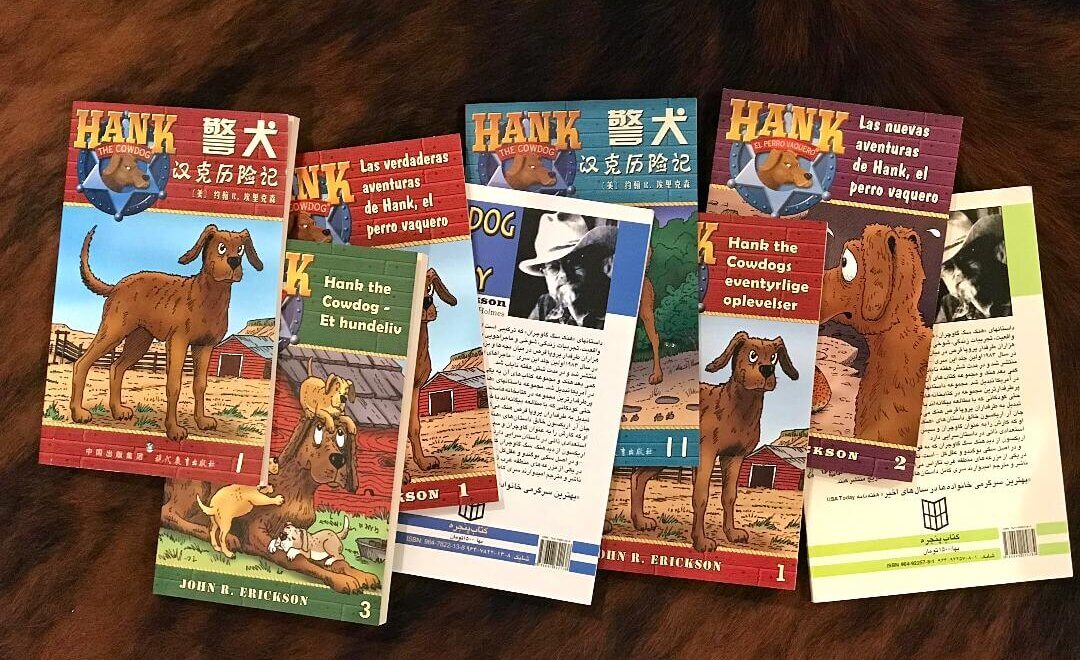

In March 1983, rising interest in the character led him to take a leap of faith and self-publish the first book in the Hank the Cowdog series. By the late ’90s, Hank the Cowdog had sold millions of copies, been translated into multiple languages, and gained worldwide popularity, even spawning a CBS cartoon adaptation.

Erickson narrated the audiobooks himself, assigning a distinct voice to each character — Hank a self-assured southern drawl, Drover a hoarse whine, Pete the Barncat cat a silky, devious purr — and sang original songs to accompany each book.

Among Hank’s Greatest Hits are Rotten Meat, Eating Bugs is Lots of Fun, It’s Not Smart to Show Your Hiney to a Bear, Cannibal Trash, and A Dog Should Smell Like a Dog.

The dog smell in question is achieved by luxuriating in the sewer.

In The Further Adventures of Hank the Cowdog, Hank explains, “That first plunge is probably the best, when you step in and plop down and feel the water moving over your body. Then you roll around and kick your legs up in the air and let your nose feast on that deep manly aroma. Your poodles and your Chihuahuas and your other varieties of house dogs will never know the savage delight of a good ranch bath.”

Ranch Life Learning

One day, between readings at an elementary school in suburban Houston, Erickson found himself with spare time on his hands and began perusing the library’s selection of books on ranching and cowboys. To his dismay, all of the books were written by authors from New York and Connecticut and distributed by Manhattan publishing houses.

“They were people who had no personal experience in that way of life, in that business,” says Erickson. “In fact, they probably got all of their information by checking The Modern Cowboy out of the library and using my hard-won experience to sell their own books, so I thought, ‘Why should these kids be reading books on ranching and cowboying by people who know nothing about it?’”

Erickson used his ranching expertise to write a five-book series on ranch life containing the same information as The Modern Cowboy, but explained through the humorous lens of Hank the Cowdog.

In partnership with the National Ranching Heritage Center at Texas Tech University, the Ranch Life Learning series has been distributed to classrooms across the state and utilized in science and social studies curricula.

Julie Hodges, Helen DeVitt Jones director of education at the center, has been working with Erickson to teach students about ranching for almost a decade.

“What he did was pretty magical,” Hodges says. “He brought a really complicated, convoluted system of ranching together in a concise, clear way that’s useable in a classroom, and magic because Hank’s sprinkled on top of it.

“As we were working with teachers and getting these books out into the world, we realized there was an opportunity to bring these books to life and give people a hands-on opportunity to learn what ranching is.”

The Cash Family Ranch Life Learning Center, which opened in October 2023, is an elaborate homage to the ranching profession and Erickson’s work. Museum visitors can explore 16 immersive exhibits with Hank the Cowdog as their guide.

Attractions include an orientation theater in which a holographic Erickson pops out of a book and introduces the exhibits, Security Headquarters in which Hank assigns missions to museum visitors, a half-acre exterior exhibit, a replica of High Loper and Sally May’s ranch house, and an outdoor amphitheater with live animal demonstrations.

“Hanging out with Mr. Erickson is like being with Elvis,” says Hodges. “He thinks I’m silly for saying that, but it’s true. You can’t walk across the parking lot without getting stopped several times, and people come up to him during book signings and tell him the most amazing stories and thank him for raising their children and grandchildren, or just tell him about how his books made a reluctant reader get into reading.”

Those children that Hank the Cowdog helped raise continue to inundate Erickson with heaps of fan mail, praising him for getting them through the Accelerated Reader program.

Earlier this year, an 86-year-old great-grandmother who had just discovered the series — and promptly read 30 of the books — wrote Erickson to thank him for the gift of laughter.

But not all the correspondence is lighthearted; occasionally, Erickson will receive a letter that brings him to tears.

“Several years ago, I got a letter from a woman who said that her daughter just loved the Hank books and that she’d contracted leukemia,” Erickson recalls. “They knew that she was dying, and what she wanted was for the family to read Hank books in her hospital room, and that was the way she passed on. That kind of knocked me down.”

Forged in Flames

The trust parents place in Hank the Cowdog, and the prominence of those books in readers’ most formative years, is of spiritual significance to Erickson.

“I’m not a preacher,” he says. “I went to divinity school for two years and decided that wasn’t my language system. But I’ve had the unusual opportunity to write stories that parents trust; parents trust me with their children, and that’s a heavy responsibility that I take very seriously. Even though you’ll find very rare references in the Hank stories to church, that’s the inspiration for what I do.”

Erickson’s church community would play a bigger role than ever in 2017, when wildfires swept through Kansas, Oklahoma and Texas and destroyed over a million acres of land, including 90% of the M-Cross Ranch.

Erickson and Kris lost their home, their guest house, childhood photos of their three children, Erickson’s writing office and library, several unpublished manuscripts and over a dozen animals, including their cowdog, Dixie.

“It was a pretty catastrophic event for us,” says Erickson. “Kris and I left home with our laptop computers, her mandolin, and the clothes we were wearing. That’s all we had the next morning, except that we lived in a loving community.

“People from our church were on our doorstep immediately with clothes and food and furniture, pots and pans and sheets and pillowcases — all the things you don’t think about. We’ve invested a lot of ourselves in this community, and it sure was gratifying when it came back to us after the fire.”

In the wake of the tragedy, Erickson quoted the Old Testament’s Book of Job: “Naked we came into this world and naked we will leave it,” adding, “but we sure will miss that house.”

He channeled his grief into several books about wildfires: Bad Smoke, Good Smoke: One Writer’s View of Wildfires; Prairie Fire, part of the National Ranching Heritage Center’s Ranch Life Learning series; and Hank the Cowdog: The Case of the Monster Fire, which he wrote in just three weeks.

Erickson and Kris have since rebuilt their home on the M-Cross Ranch, including the bunk house where Erickson spends his mornings, thinking up new adventures for Hank and Drover and chuckling to himself as he types.

“I find Hank endlessly fascinating and funny,” Erickson says. “When I write those looney conversations between him and Drover, I laugh out loud.”

These days, when he isn’t writing books and articles, composing songs, tending to cattle or voicing Old Man Wallace, the curmudgeonly buzzard, in the wildly popular Hank the Cowdog podcast narrated by Matthew McConaughey, Erickson is performing songs on his banjo, accompanied by Kris on her mandolin, in venues all over the country.

But despite Hank’s meteoric rise to fame in the ’80s and his unwavering popularity in the decades since, one thing has remained the same.

“When I step off the plane in Amarillo,” Erickson says, “boy, am I glad to be back home.”

—-

Elyssa Foshee Sanders is a freelance writer from Lubbock.

###

This story first appeared in the December 2023 issue of The Cattleman magazine.