Kellie Curry Raper, Oklahoma State University Extension Livestock Economist

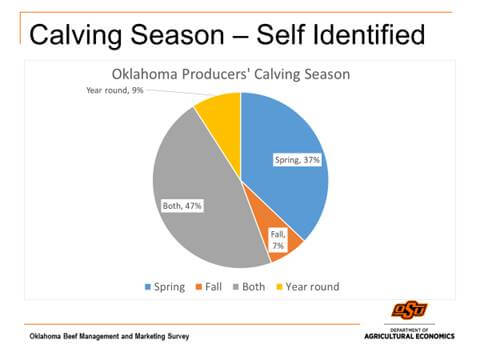

Among cow-calf producers, breeding season for the herd varies from a 30-day window to year-round. The chart below reflects calving season decisions reported by producers through the Oklahoma Beef Management and Marketing Survey in 2017. When producers were asked, 91% reported a defined calving season, with nearly half reporting both a fall and spring season.

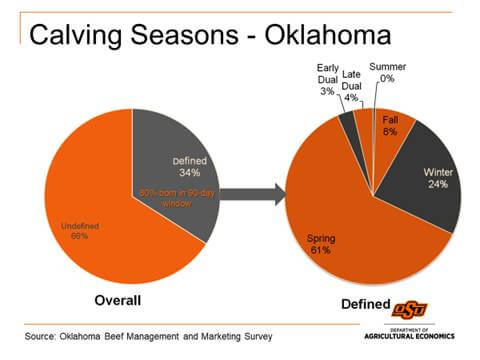

However, when compared to the same producers’ percentages of calf crop born by month, only 34% had a defined calving season, defined as 80% of calves born in a 90-day window, or 80% of calves born across two distinct 90-day windows, i.e. dual seasons. This result is similar to the 2017 National Animal Health Monitoring System data, where 58.7% of operations had no set season.

Does a defined calving season – and thus a defined breeding season – matter? Let’s take a look.

Year-round calving – Why shouldn’t the bull be on continuous duty? If you want to keep cows on an annual calving cycle, they should be rebred within 80 days after calving. If the bull is a constant presence, females with reproductive issues that should be culled may take longer to detect. And the longer those issues take to detect, the more likely a cow misses a calving season – and the producer has cost associated with the cow, but no revenue to show for it. A defined breeding season highlights any breeding issues more quickly, allowing producers to select cows over time that return the highest value. It also facilitates more focused attention on bred cows and heifers as calving season starts, because there are fewer surprises as to the timing of births.

That’s only one piece of the puzzle. Here are a couple more.

Impact on Cost per Cow – Though Ramsey et al’s (2005) study of standardized performance data from 394 ranches in Texas, Oklahoma, and New Mexico is more than 15 years old now, we can still learn from it. Note that breeding season length in their study ranged from extremely short (less than one month) to 365 days, that is, year-round presence of the bull. In the ranches represented, each additional day in the breeding season decreased average pounds of calf weaned per cow per year by 0.16 pounds and increased the annual cost of producing 100 pounds of weaned calf by 4.7 cents. A year-round breeding season (365 days) would result in 45.82 fewer pounds of calf per cow per year on average than a 75-day breeding season. In 2004, cost per hundredweight of weaned calf was $13.63 higher for producers with year-round breeding seasons compared to those with 75-day breeding seasons. Producer price indices for September 2004 and September 2022 indicate those costs can be multiplied by 1.5 to get today’s cost, estimated at $20.45 per hundredweight, or an additional cost of $112.48 for a 500-pound weaned calf.

Impact on Calf Value –What does breeding season have to do with calf value? A relatively narrow calving window facilitates recommended calf management practices, such as vaccinations, extended weaning, and other health management practices because calves are in a narrower age range and ready for practice implementation at the same time. This also facilitates marketing larger lots of uniform calves at sale time. This has value, even in small increments. Increasing lot size from a one-head lot to a five-head lot increased calf value on average by approximately $17/head in Oklahoma auctions with an increase of approximately $25/head for a ten-head lot over a one-head lot (Mallory, et al. 2016). This suggests that even small producers can benefit from a strategic calving season.

The Takeaway

If you haven’t recently contemplated how your breeding and calving seasons contribute to the value of your cattle operation, take some time to consider whether there are incentives to change it. If you want hard data, track cost and value for your own operation and compare it to alternative scenarios. Decision making on the ranch is a continuous feedback loop – and it’s never out of season!

Mallory, S., E.A. DeVuyst, K.C. Raper, D. Peel, and G. Mourer. “Effect of Location Variables on Feeder Calf Basis at Oklahoma Auctions.” Journal of Agricultural and Resource Economics 41(2016):393-405.

Ramsey, R., D. Doye, C. Ward, J. McGrann, L. Falconer, and S. Bevers. “Factors Affecting Beef Cow-Herd Costs, Production, and Profits.” Journal of Agricultural and Applied Economics 37(2005):91-99.