Asian longhorned tick continues its cross-country spread.

By Jena McRell

Simply hearing the word tick often makes skin crawl. The tiny, blood-feeding parasites are difficult to see, slow to move and pose significant health risks to humans, livestock and a multitude of other hosts.

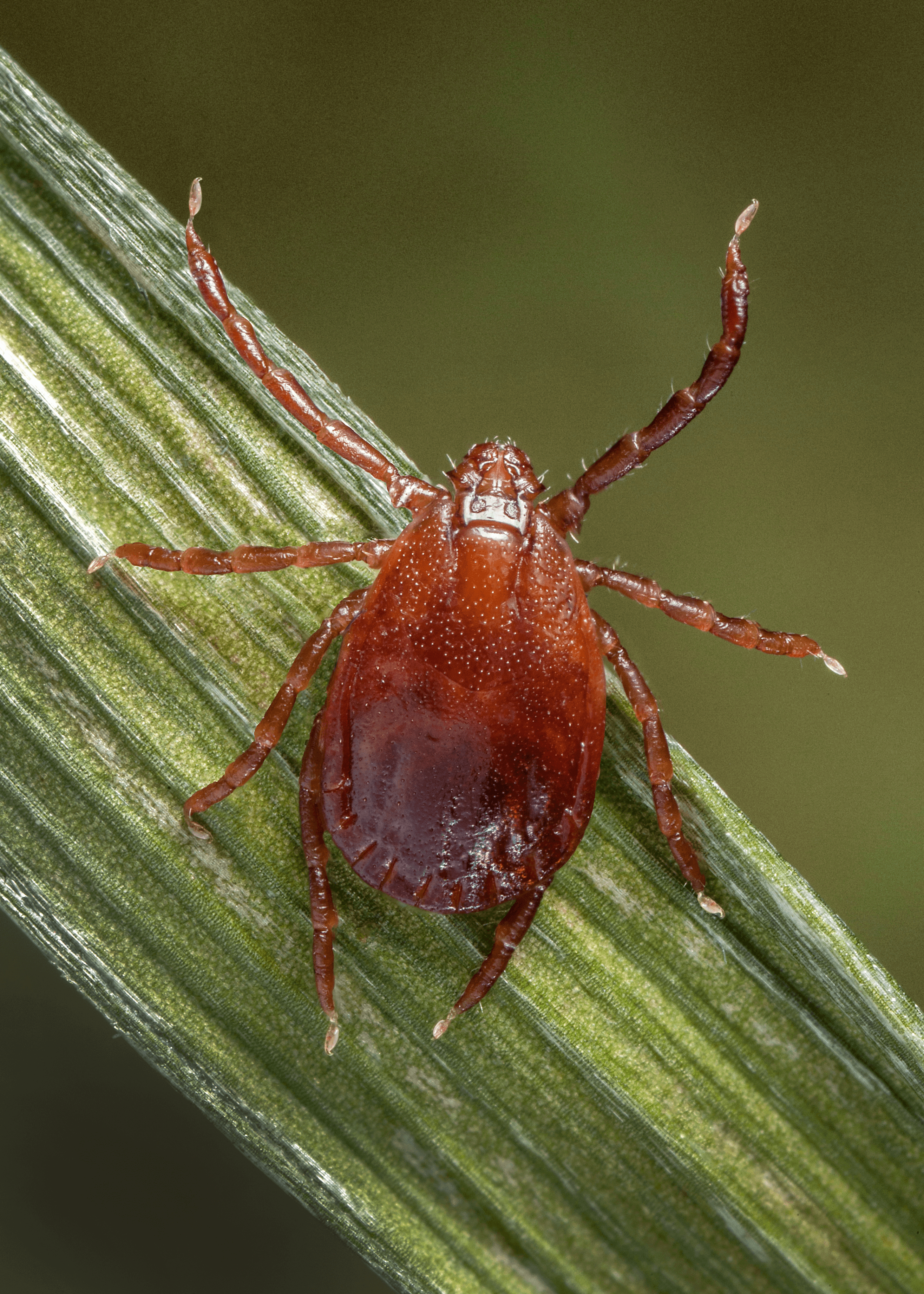

Recently, the cattle industry has had sights on a newly emerging, exotic species — the Asian longhorned tick, Haemaphysalis longicornis.

First identified in the U.S. about six years ago on a sheep in New Jersey, the tick is native to Japan, China, parts of Russia and Korea. The multi-host tick, roughly the size of a sesame seed, has been found on cattle, horses, dogs, goats, deer and other wildlife, including birds and rodents.

The Asian longhorned tick is concerning to cattle producers because it reproduces quickly and has the potential to spread a disease pathogen resembling bovine anaplasmosis.

Striking up a population of ticks in a new area or within a herd requires only the presence of one female. They reproduce asexually without a male, an oddity among ticks currently found in the U.S., and lay thousands of eggs at a time.

To date, the Asian longhorned tick has been confirmed in 19 states, but not yet in Texas, Oklahoma or the Southwest. Experts agree, it is likely on its way.

Keeping watch

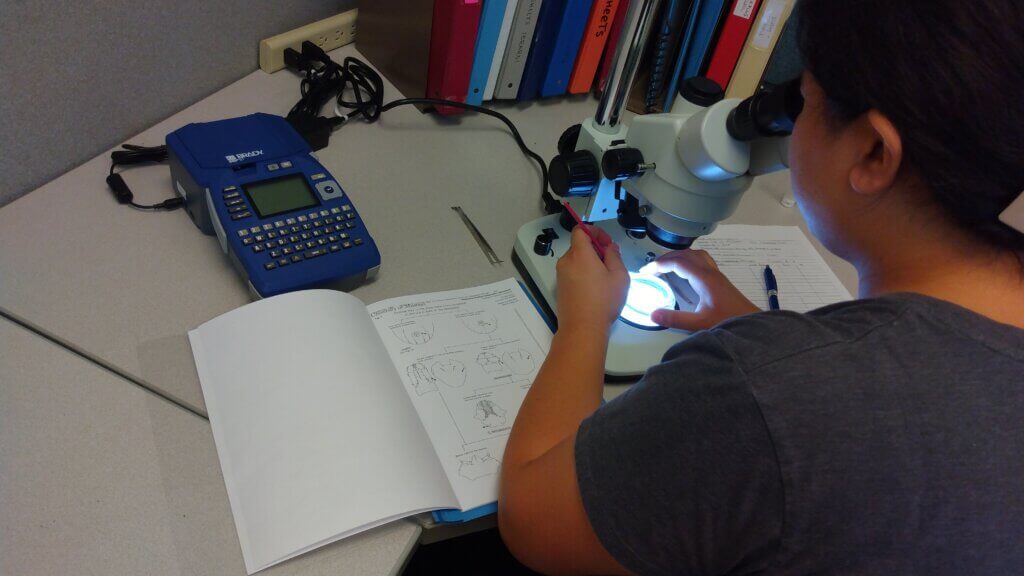

From her Stephenville office, Texas A&M AgriLife Extension Specialist Sonja Swiger loads a USDA dashboard for tracking the Asian longhorned tick. Swiger, who is also a professor with a doctorate in entomology, studies how to manage nuisance biting flies and disease-vectoring insects impacting livestock, wildlife and humans.

Two counties in Arkansas with confirmed cases of the Asian longhorned tick are the closest in proximity to Texas. Although, more concerning are three known cases in Missouri, a frequent region for livestock exchange.

“The Asian longhorned tick is continuing to move, but it has been very slow,” Swiger says of the reddish-brown parasite most closely resembling the native brown dog tick, Rhipicephalus sanguineus.

Since it is not host-specific, the Asian longhorned tick has been found on a number of different species in the U.S. and its countries of origin. It is also a three-host tick, meaning it moves from host to host throughout its main life stages, which can take anywhere from roughly 6 months to a year.

“When it is growing, it will find a different host for each of those stages — larvae, nymph and adult,” Swiger says. “Because it can reproduce quite quickly and at high densities, you can get multiple stages on a single host, and that becomes problematic.”

Most ticks are only on an animal for a couple days or weeks, she explains, for however long it takes them to feed. Oftentimes, they are found in the environment. Along the edges of pastures and in areas overgrown with brush.

“With the Asian longhorned tick, it could go anywhere in the state,” Swiger says. “It’s expected it will be brought in by animal movement — whether that’s cattle or a domesticated dog or cat, there is no way to tell. It is really a lot of uncertainty, which makes it tough.”

Heightened risk

In addition to general animal health and production threats associated with ticks and tick-borne diseases, the Asian longhorned tick has captured the attention of cattle producers and veterinarians because of a potential pathogen, the Ikeda strain of Theileria orientalis, it is known to carry.

Not generally found in the U.S., this particular strain of Theileria attacks red blood cells in cattle and symptoms mimic those of bovine anaplasmosis.

That’s how Rosalie Ierardi, an anatomic pathologist at the University of Missouri College of Veterinary Medicine, happened on the state’s third confirmed identification of the invasive longhorned tick in August 2022.

She was conducting field research in north central Missouri, searching for the American dog ticks, Dermacentor variabilis, known to transmit bovine anaplasmosis. In their search, they uncovered two nymphs of the Asian longhorned tick.

“The finding attracted attention because it was the farthest north in the state that this tick had been identified at that time,” says Ierardi, mentioning the other two findings were confirmed around Kansas City and Springfield, Missouri.

While the Asian longhorned tick does not transmit bovine anaplasmosis, like the winter tick, or Dermacentor albipictus, does in Texas and the Southwest, symptoms of cattle infected with the Ikeda strain of Theileria orientalis can be similar.

Cattle can quickly become anemic, may have a high fever, pale mucous membranes, and elevated heart and respiratory rates. Other symptoms include jaundice, weakness, spontaneous abortions and even death.

Pregnant heifers, calves and other animals with weakened immune systems are particularly susceptible to this and other tick-borne diseases.

“One thing we’ve tried to consistently message to producers here in Missouri is that, if you have what appears to be an increase in cases of anaplasmosis or you are seeing cases in younger calves than you typically do, consider getting in touch with your local veterinarian and testing for this Theileria,” Ierardi says. “There’s really no way to tell them apart without doing a blood test.”

She reminds cattle raisers the presence of the Asian longhorned tick alone does not mean animals will become sick. It’s the organism the tick carries that causes the destruction of red blood cells and related symptoms.

“Once you have the tick established, then you have to be careful, because if you had some cattle come in that were infected, then the tick could spread it to other cattle,’” Ierardi says. “But just having the tick doesn’t automatically mean you have the Theileria.”

Beyond the herd, human health risks associated with ticks are also a concern.

Swiger says laboratory studies have shown the Asian longhorned tick does not transmit Lyme disease, but it is possible for it to relay Rocky Mountain spotted fever. Although, no cases of the latter have been confirmed.

“If we are going to give the Asian longhorned tick any gold stars, we will give it that one,” she says. “Because we don’t need another tick carrying Lyme disease.”

Prevention and control

Texas A&M AgriLife Extension reports an Asian longhorned tick outbreak would add to the $162 million in economic hardship ticks already have on the industry.

Six species regularly affect cattle in the region: Lone Star tick; black-legged tick; winter tick; Gulf Coast tick; brown dog tick; and the American dog tick.

“While we are seeing tick expansion with even our native species moving further north and west, it does take time,” Swiger says. “So that is not something that happens within a few months. It takes years for those changes to occur.”

Ticks alone can pose problems, damaging the hide or causing wounds on an animal. But with any species, larger tick loads can be a serious threat to livestock productivity. If animals are not eating enough or rapidly losing blood, growth is limited and could lead to anemia.

“Most larger cattle can handle tick loads,” Swiger says. “But when you have younger or weaker cattle with lots of ticks, they become anemic really fast and it could be detrimental to them.

“It is important to keep those numbers down, so that you are not impacting your own profits and even maybe your neighbor’s profits by having ticks in an area that’s close enough that they can get to other animals.”

Both Swiger and Ierardi stress the importance of checking newly purchased cattle before introducing into the herd.

“We recommend doing tick checks whenever you bring cattle in to work them,” Swiger says. “Look around their ears, heads, underneath and between their legs. And a lot of ticks will go by the tail.”

The Asian longhorned tick is susceptible to the same repellents and anti-tick treatments used within the industry. Insecticide ear tags are a proven preventative method for ticks attaching on the upper half of animal; along with using Prolate/Lintox applied as a whole animal spray.

Keeping pastures mowed when possible and avoiding overgrown grasses helps remove tick habitats, as well.

“Ticks can feed on a variety of wildlife species,” Ierardi says. “Even if someone was being really careful and then somehow they ended up finding this tick on their farm — they didn’t do anything wrong. It could literally have come in on a bird or some other type of wildlife species.”

Cattle raisers are encouraged to report any questionable ticks they may find on their animals or property. Ticks can be placed in rubbing alcohol and submitted to a local veterinarian or Texas A&M AgriLife Extension office for testing.

“We have a lot of people who work in the tick field,” says Swiger, referencing AgriLife Extension, Texas Animal Health Commission and USDA. “We are always willing to take samples, so we can be prepared for what we need to do when it’s our turn.”

This story first appeared in the August 2023 issue of The Cattleman magazine.